Archbishop Romero, his people and Pope Francis

A quarter of a million people attended the beatification ceremony in El Salvador for Archbishop Oscar Romero on 23 May 2015. A huge crowd chanted songs and carried banners as a procession moved from the cathedral, where Archbishop Romero’s tomb lies in the crypt, to Salvador del Mundo (Saviour of the World) Square in the centre of San Salvador. Here the Vatican envoy Cardinal Angelo Amato presided over the beatification ceremony.

These were the opening images in a new film about Romero, subtitled ‘Archbishop Romero, his people and Pope Francis’, which had its first UK viewing in London on 1 July. It will probably be entitled ‘Making Amends’ in its English version, suggesting that Romero is finally being recognised as a martyr, after Pope Francis declared two years ago that he was killed “in hatred of the faith” and not, as some contended, for political reasons.

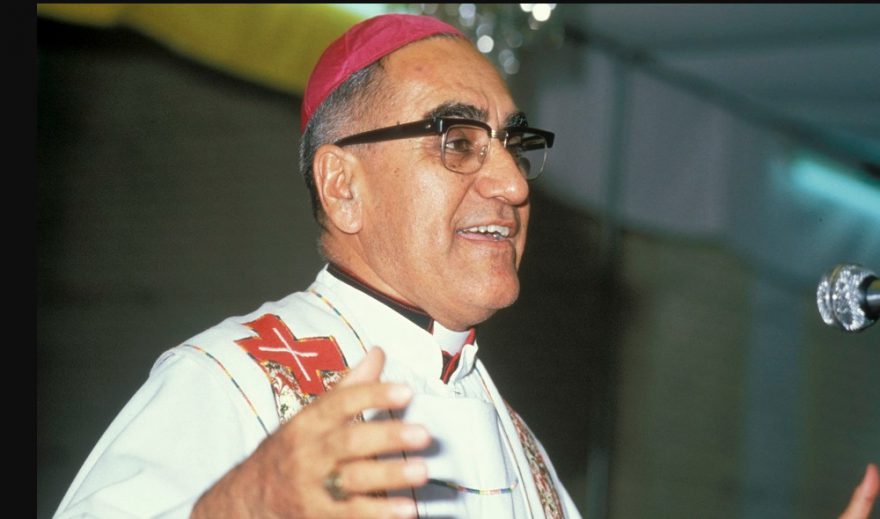

Beatification is the penultimate step before Archbishop Romero is, hopefully, declared a saint. He was shot dead by a marksman as he celebrated Mass in a hospital chapel in San Salvador on the evening of 24 March 1980. The film contained much new footage of Romero, particularly from the last three years of his life when he challenged the violence going on in El Salvador. He regularly visited poor communities and affirmed young people who were growing up amidst poverty and repression. The film showed spontaneous clapping as he walked among people, standing close to them and entering their homes. A real love between Romero and the Salvadorean people was evident. “The Church is trying to give them a little hope” he said.

His homilies in these years were a dynamic challenge to the military-backed government, especially since they were broadcast nationwide on the Church’s radio station. When the US-backed Salvadorean army used death squads and torture to silence leftist movements demanding change, he was not afraid to speak out in his weekly sermons. “The law of God which says thou shalt not kill must come before any human order to kill; it is high time you recovered your conscience,” he said in his last homily in 1980, calling upon the national guard and police to stop the violence. “I implore you, I beg you, I order you in the name of God: Stop the repression” he urged. That sermon, interpreted as calling for insubordination, cost him his life. A day later, while saying Mass, he was shot through the heart by a single bullet.

The film records those who knew him well, giving insight into his character. Monsignor Ricardo Urioste, who died last year, told us that that when Romero was chosen as archbishop he did not attend his swearing in. “I thought he was not a good choice for archbishop” he said “and that he was appointed to control the priests who were interested in Medellin”, a reference to the 1968 meeting of the Conference of Latin American Bishops which stated that the Church should make a “preferential option for the poor” and tackle “the institutionalised violence of poverty”. Theologian Jon Sobrino reported on the change evident in Romero just a month after his appointment, following the murder of his friend, the Jesuit priest Rutilio Grande, on 12 March 1977. “He was shocked at what was happening to poor people, catechists and priests” reported Fr Sobrino, “and was outraged at the bumper stickers put out by the military, ‘Be a patriot, kill a priest’”.

But Romero’s adversaries were not just in the military and the affluent families who controlled El Salvador. His focus on social justice, condemning the concentration of power and wealth in El Salvador, and speaking out against structural violence, attracted criticism from his fellow bishops who complained to Rome that he had Marxist leanings. Roberto Cuellar, a lawyer who was hired by Romero to run a free legal-assistance office in San Salvador, reported on Romero’s sadness when his fellow bishops mocked him and laughed in his face “like hyenas”, and he was so upset he asked Romero’s permission to leave the meeting. When Romero travelled to Rome in 1979, with copious documentation regarding victims of repression to show to Pope John Paul II, the latter told him, “you should not have come to Rome with so many documents”. In a difficult meeting, the pope expressed concern that the priests killed were linked to the guerrilla movement and that Romero was not making enough effort to get along with the Salvadorean government. Romero not only continued his challenge but wrote a letter to President Jimmy Carter begging the United States to stop sending weapons to the Salvadorean military government which were used to repress the people. Pope John Paul II clearly had a change of heart when he visited El Salvador in 1983 and 1996 and both times asked to visit Romero’s tomb and pray before it. Thereafter he gave his full support to Romero’s beatification. Unfortunately, many senior officials in the Curia did not.

Archbishop Romero comes across as a brave man of whom the Church can rightly be proud for his defence of the poor, and his call for justice and peace. Was he ever fearful that he too would die a violent death? The film contains an interview where he says: “I am mildly fearful, but not in a paralysing way that affects my work.” He was one of over 70,000 people who died during El Salvador’s Civil War, and a UN report records that approximately 85% of all killings of civilians were committed by the Salvadorean armed forces and death squads.

The film highlighted things that were new to me – for example, Romero consulted widely before delivering his explosive sermons, and he spent the final morning of his life on a trip to the beach with some of his priests and a packed lunch!

Several Latin American cardinals in the Vatican had blocked his beatification for years because they were concerned his death was prompted more by his politics than by his preaching. But with Pope Francis the process has been “unblocked”, as he himself put it.

Now that Romero is beatified the next stage is canonisation. However, he has been a saint by popular acclaim in Latin America ever since his killing. Roberto Cuellar told of walking down a street in San Salvador on the evening Romero died and finding a group of beggars who said, “they have killed the saint”. He reports that as being “the first time I heard him called a saint”. At his beatification Pope Francis said: “In this day of joy for El Salvador and also for other Latin American countries, we thank God for giving the martyr archbishop the ability to see and feel the suffering of his people”.

The film was introduced by Julian Filochowski, the chair of the Archbishop Romero Trust, who has lobbied tirelessly for the canonisation of Romero. He knew the archbishop and worked with him in the late 1970s. He was present at the beatification two years ago, just as he had been at his funeral in 1980 – where the military dropped smoke bombs on mourners leading to around 40 deaths. In the 1980s, during his visits to El Salvador as Director of CAFOD, he made a photographic record of the mutilated corpses left out on the streets of San Salvador daily by death squads. Julian is one of many who have long regarded Romero as an extraordinarily meaningful figure far beyond El Salvador, and an important witness from the Church to the world for the 21st century. When Bishop Gregorio Rosa Chavez was recently elevated to become El Salvador’s first cardinal, one of the first things he did was to say Mass at the tomb of Blessed Oscar Romero and say, “I dedicate this appointment to Archbishop Romero”.

Taking questions after Saturday’s preview from assembled Catholic journalists and friends of the Archbishop Romero Trust, filmmaker Gianni Beretta explained that the likely title, ‘Making Amends’ refers to the “moral reparation” of recognising Romero, nearly four decades after his death, as a champion of the common good, of the same standing as Martin Luther King, Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela. It was pointed out that the date of his killing – 24 March – is now the United Nations ‘Day for the Right to the Truth Concerning Gross Human Rights Violations and for the Dignity of Victims’. The day is explicitly linked to Archbishop Romero and could be described as a secular canonisation.

Look out for details of the film’s availability on the website of the Archbishop Romero Trust www.romerotrust.org.uk

As part of celebrating the centenary of Archbishop Romero’s birth in 1917, the Archbishop Romero Trust has organised a Centenary Pilgrimage to El Salvador in November. Places are still available:

www.romerotrust.org.uk/news/romero-centenary-pilgrimage-el-salvador-2017

Romero centenary events are available at:

www.romerotrust.org.uk/news/romero-centenary-events

Blessed Oscar Romero, bishop and martyr, defender of the poor, Pray for Us.